Adventures in Category Theory - The algebra of types

Last time we have become familiar with the very basics of category theory, and even had a look at some scala code covering isomorphisms. It is time for looking at products, coproducts and the algebra of types.

Universal construction

Universal construction is common in category theory, it is used to define objects in terms of their relationships to other objects. First, we find a pattern, a shape consisting of objects and morphisms, then look at all its occurrences. There might be many, so we have to find a way to rank those so we can pick the best possible candidate, the one that could be considered the best fit, the more authentic, if you like. Let’s meet some of these universal constructions!

Product

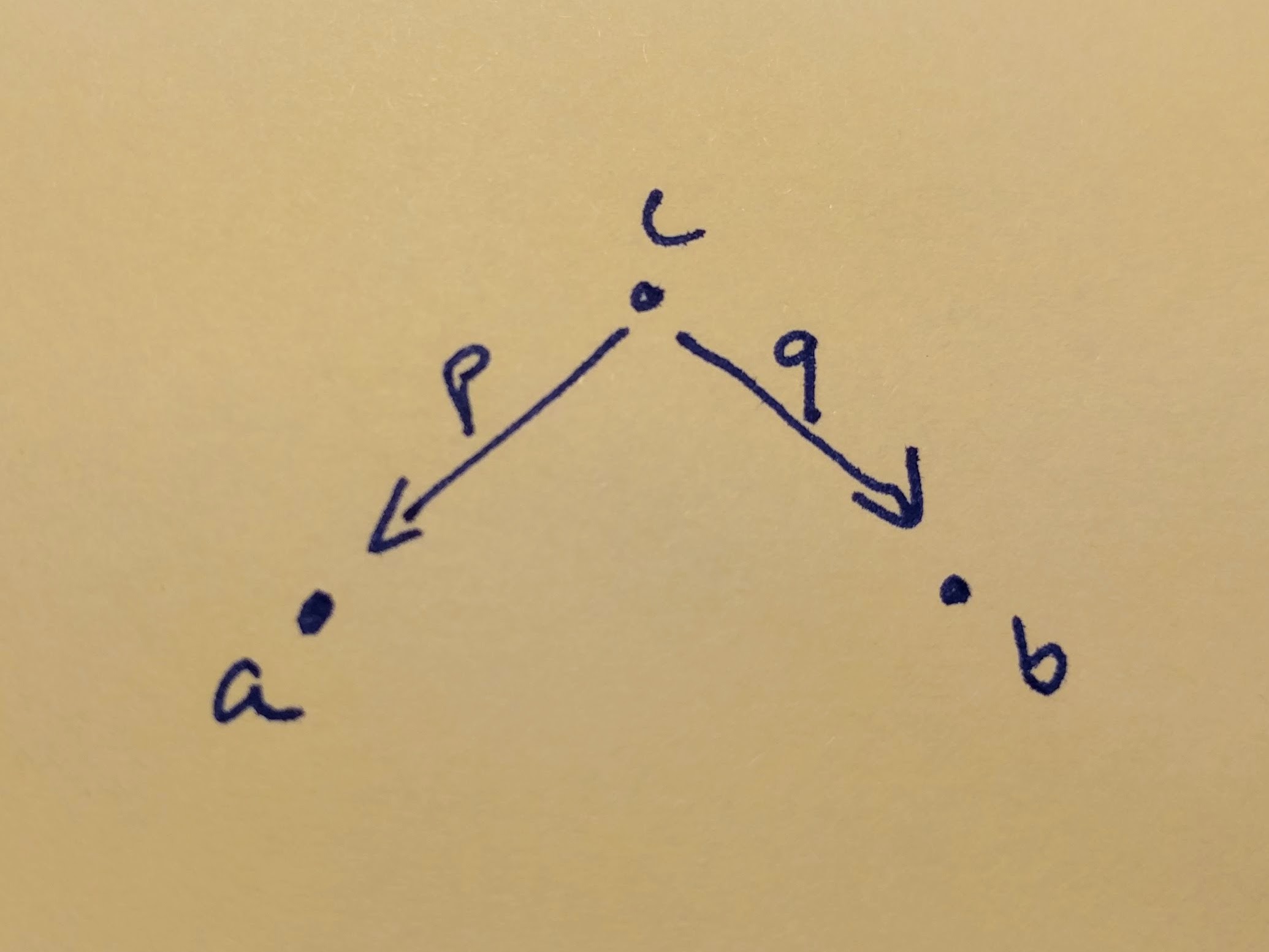

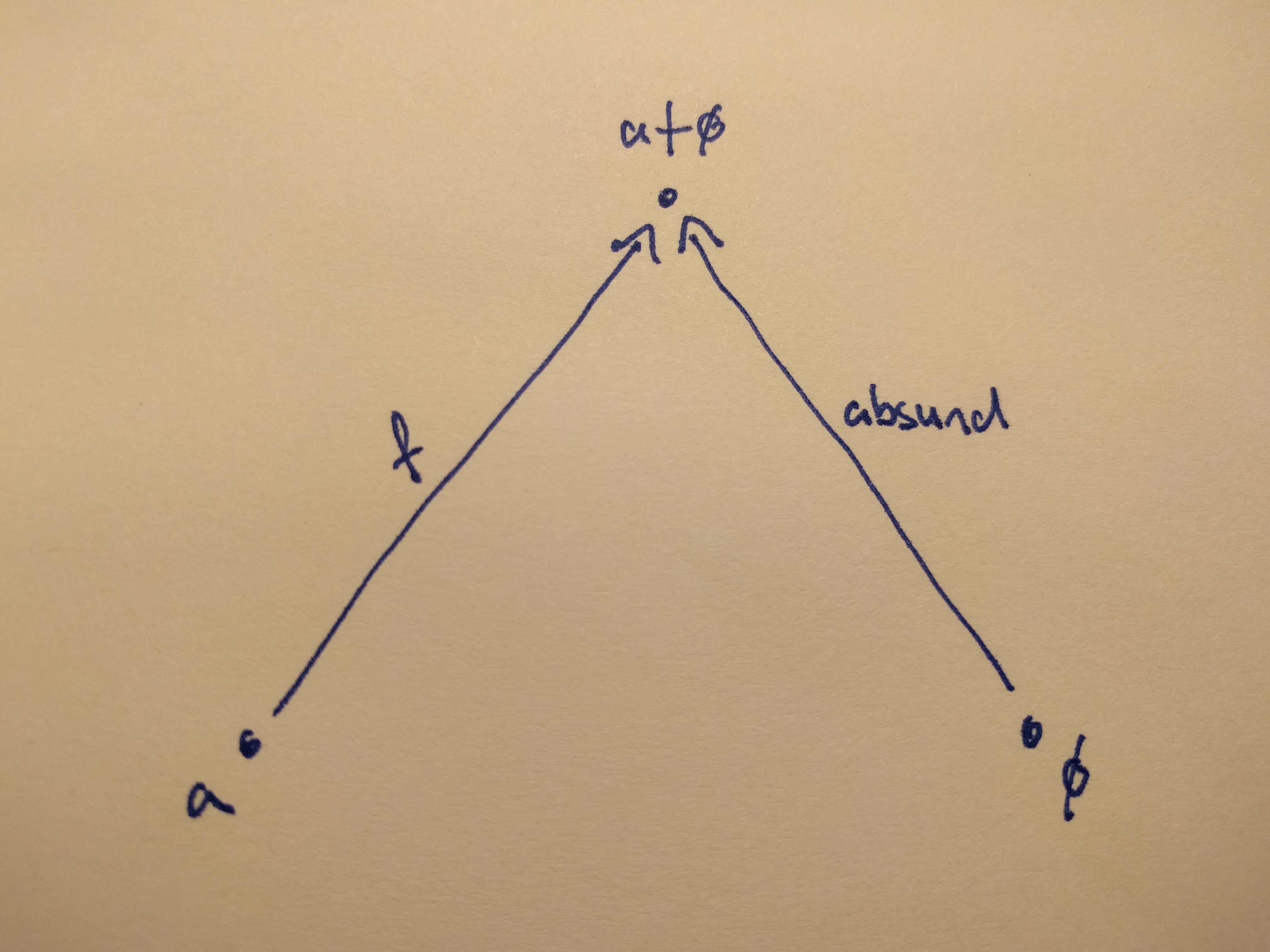

The pattern is like this:

So we say an object is good candidate for being a product of two other objects, if there are two morphisms, two projections to them, which picks the first and the second element of the product. There might be many such candidates for any two given objects and the best one is which has incoming arrows from all the other ones, so we could define the other projections by composition. (Note, that there might be many such ‘best’ candidates too, but that means, that they have arrows toward each other as well, so they are isomorphic!)

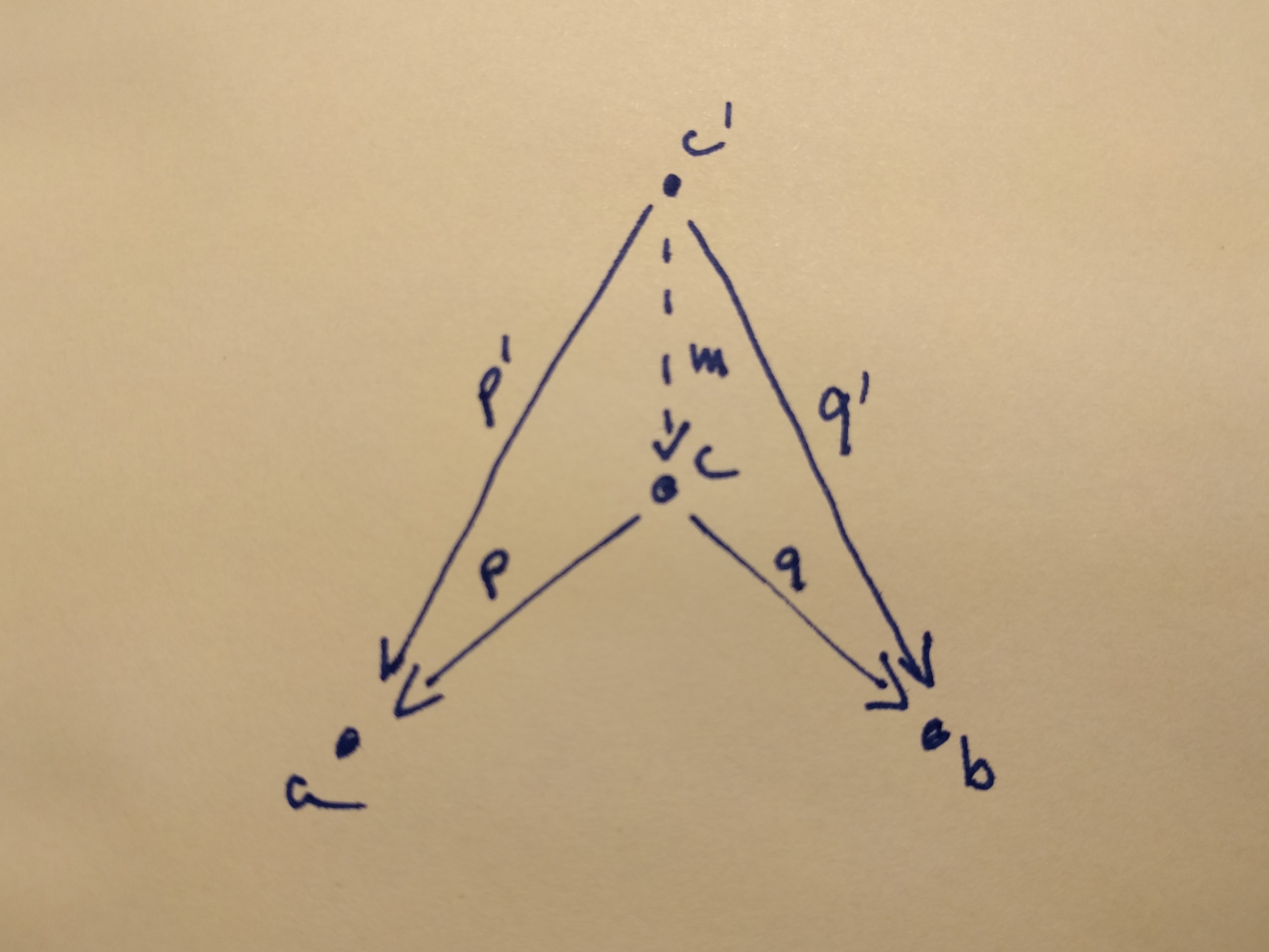

A product of two objects

aandbis the objectcequipped with two projections such that for any other objectc'equipped with two projections there is a unique morphismmfromc'tocthat factorizes those projections.

On this figure: p' = p ◦ m and q' = q ◦ m

The canonical product type is the Tuple2 in scala. It just pairs two types together. We will use the type alias * for it, because product is like multiplication, right?

object Product {

type *[A, B] = (A, B)

def projectFst[A]: A * _ => A = _._1

def projectSnd[B]: _ * B => B = _._2

}

import Product._

Coproduct

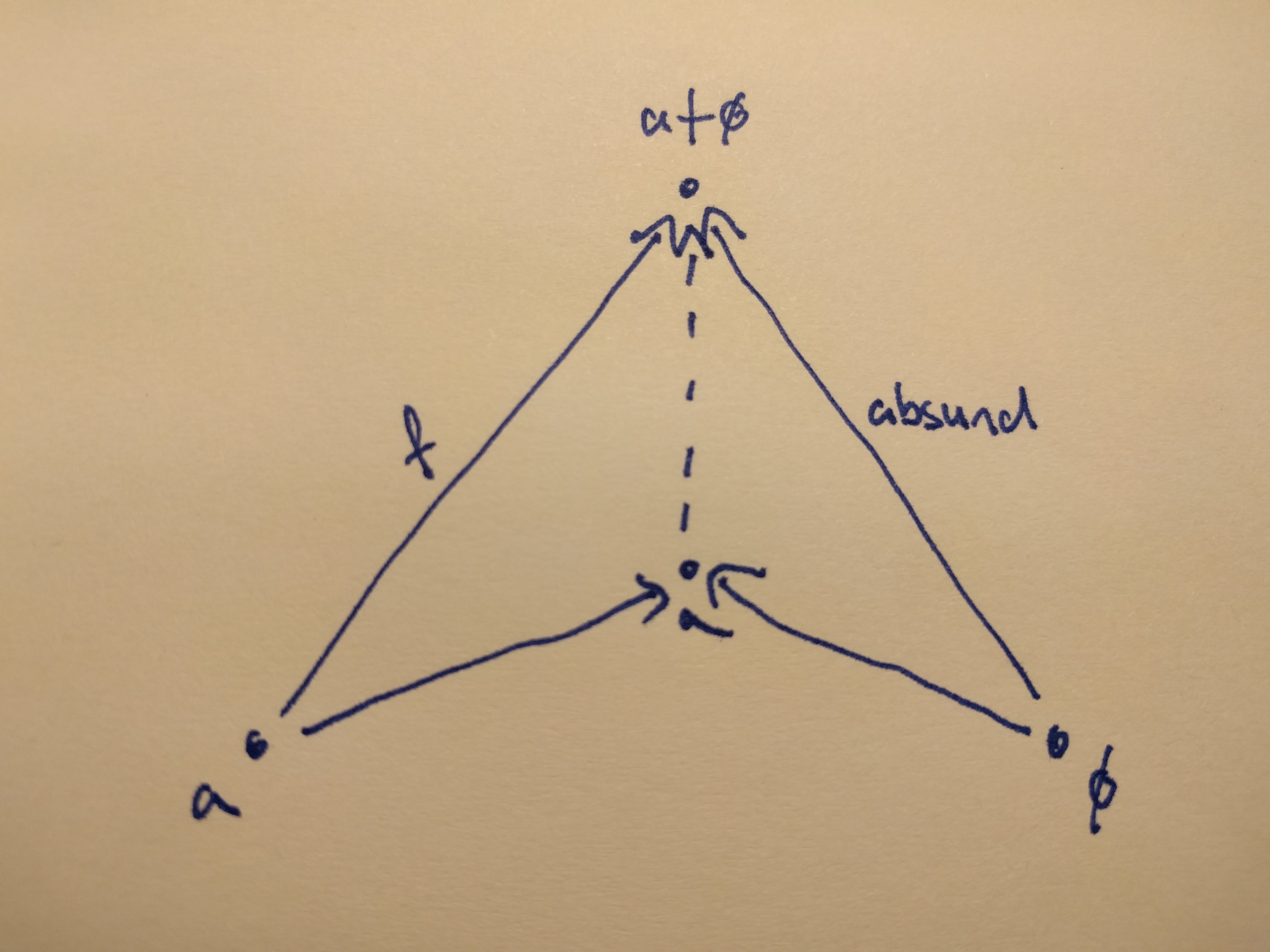

In category theory, every construction has a dual, an inverse. If we invert the arrows in the definition of a product, we end up with the object c equipped with two injections from a and b. Ranking two possible candidates is also inverted c is a better candidate than c' if there is a unique morphism from c to c' (so we could define c'’s injections by composition)

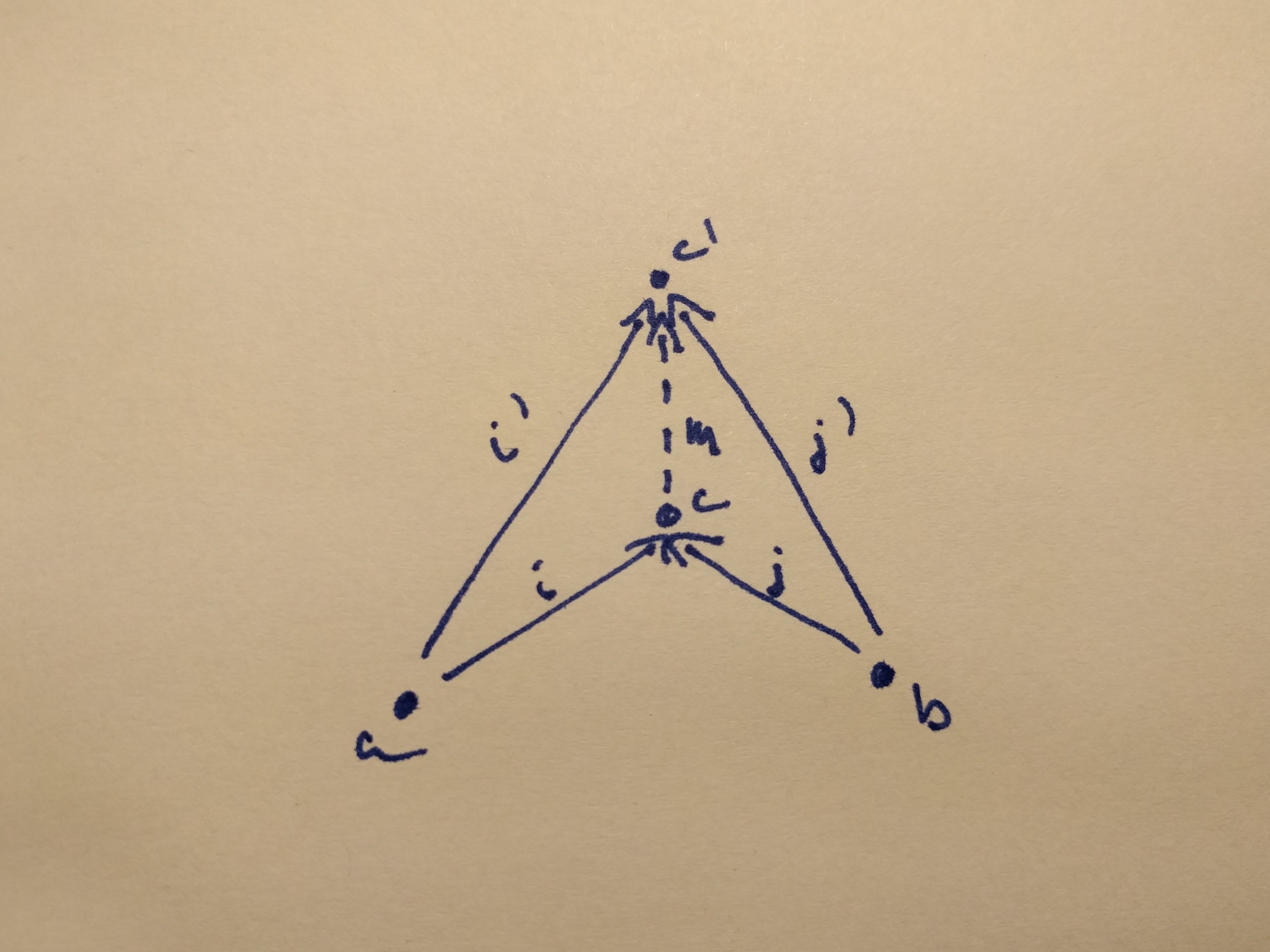

A coproduct of two objects

aandbis the objectcequipped with two injections such that for any other objectc'equipped with two injections there is a unique morphismmfromctoc'that factorizes those injections.

On this figure: i' = m ◦ i and j' = m ◦ j

If our objects are sets (as they are in the category of types and functions) then the coproduct is the disjoint union of two sets. It either has an element from one or the other.

The canonical implementation in scala is the Either type. We will use the type alias + for it, because they are also called sum types, and indeed, coproduct acts as addition in the algebra of types.

object Coproduct {

type +[A, B] = Either[A, B]

def injectLeft[A, B]: A => A + B = Left(_)

def injectRight[A, B]: B => A + B = Right(_)

}

import Coproduct._

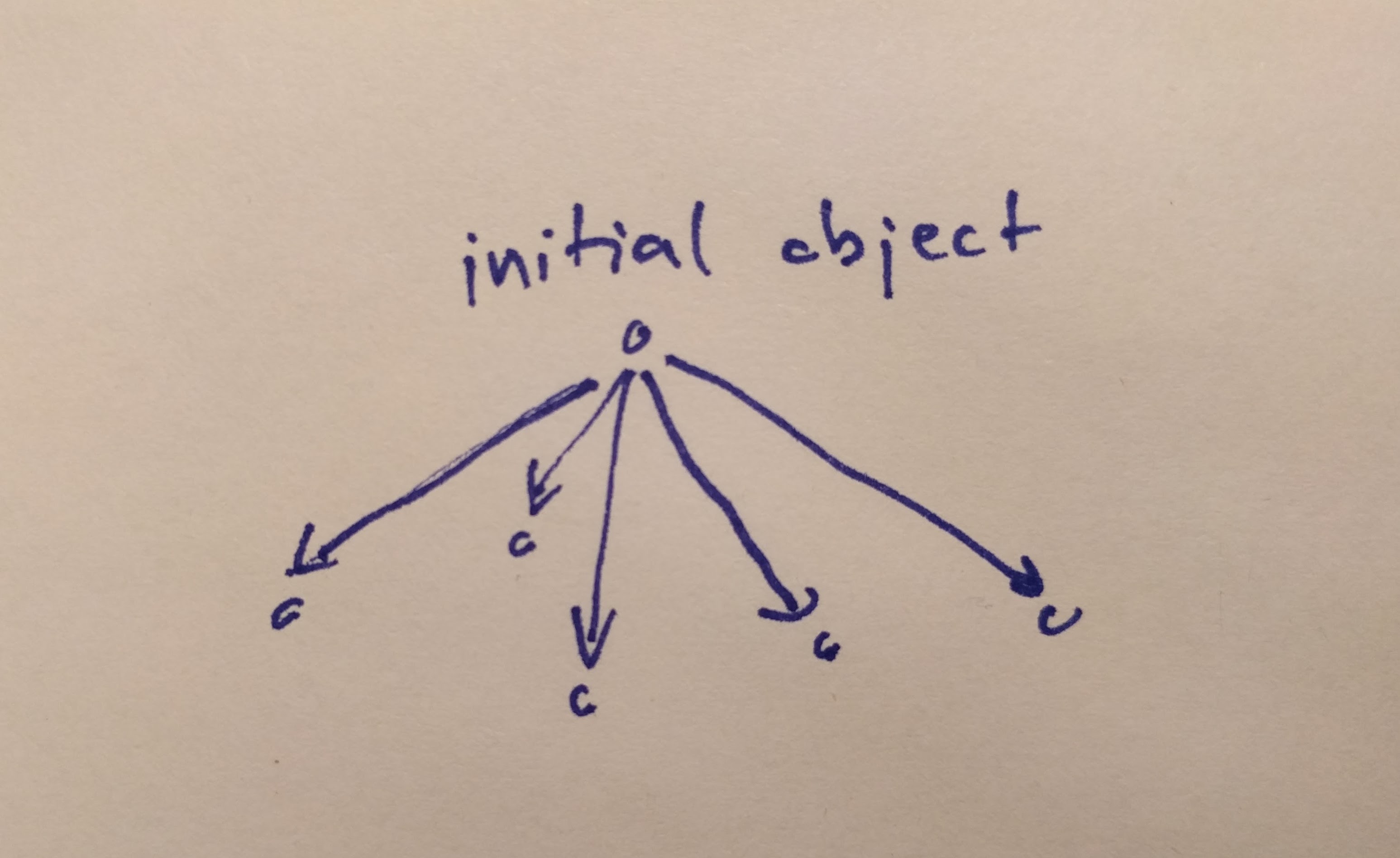

Initial objects

An initial object is the object that has a unique arrow to all the other objects in the category. There might be no initial object in a category, there might be many such object. If there are more than one, then they are isomorphic (because all of them has arrows to all other objects and therefore to each other as well).

The initial object is the object that has one and only one morphism going to any object in the category.

Again, thinking about types as sets helps here too. In the category of sets, the initial object is the empty set. What type do we know that has no possible values, a type that is uninhabited? In Haskell, this is the type Void, in scala, this could be Nothing.

def absurd[A]: Nothing => A = ???

Terminal objects

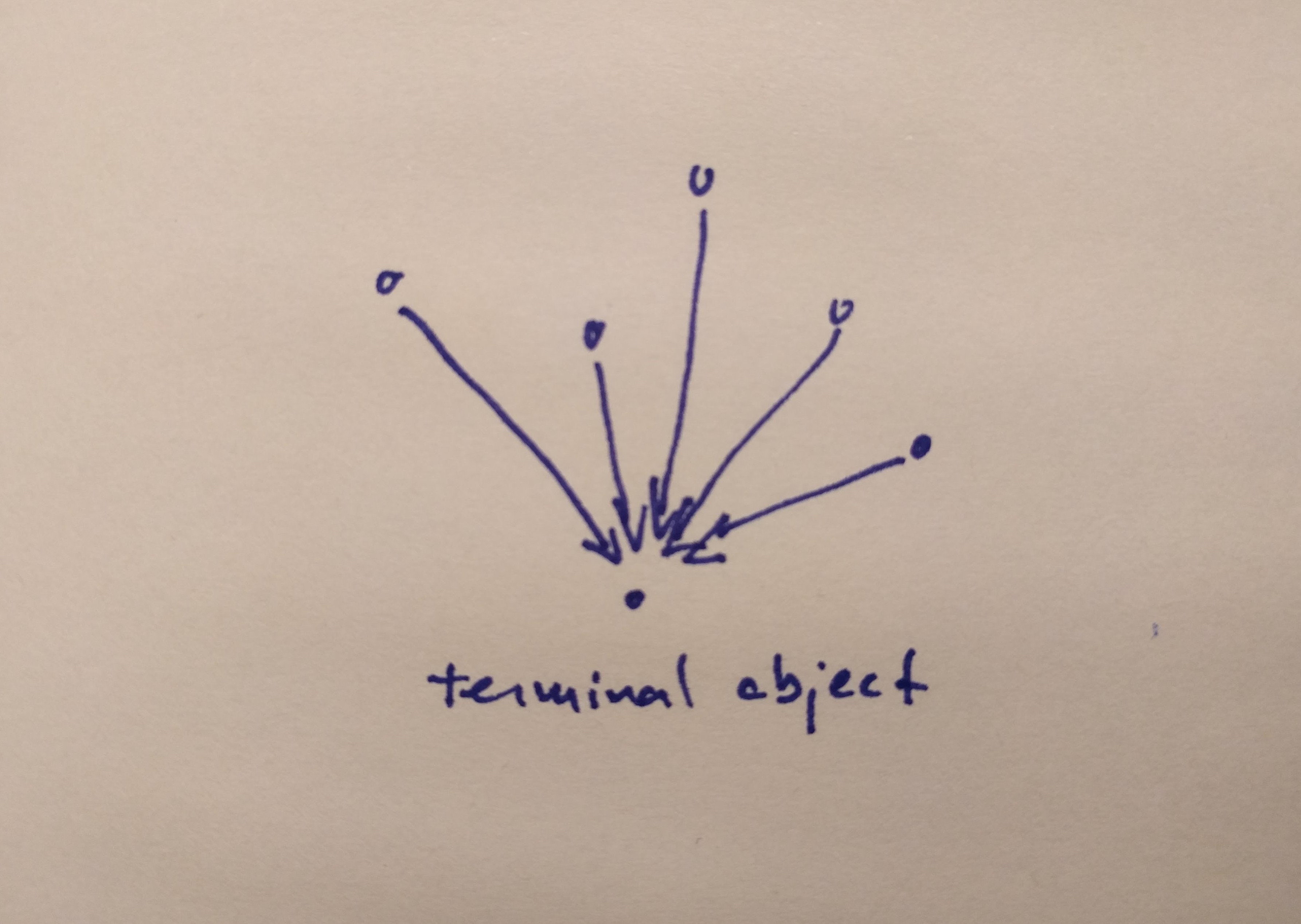

Reverse the arrows of the initial object, meet the terminal object.

The terminal object is the object with one and only one morphism coming to it from any object in the category.

In the category of sets, this would be the singleton set. What is a type that has only one value? Let’s use Unit for that! The arrow is called unit as well. Here, I provide an implementation too.

def unit[A]: A => Unit = _ => ()

Now let’s take a look at some crazy ideas that our objects behave like numbers when we multiply them together with products or when we add them with sums (aka. coproduct).

Algebraic properties of products

Commutativity a * b = b * a

So we want to prove here, that the two scala types A * B and B * A are somehow equivalent. They are obviously not the same, but that is fine as long as they are isomorphic. What we need to do is swap the elements of a pair, it sounds fairly easy:

def swap[A, B]: A * B => B * A = {

case (a, b) => (b, a)

}

Now, define the isomorphism and prove it with with the method we defined last time in the isomorphism section

implicit def commutativityForProduct[A, B] = new Isomorphism[A * B, B * A] {

def a2b = swap

def b2a = swap

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String * Int, Int * String].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Associativity a * (b * c) = (a * b) * c

Replace the *-s with ,-s above in our heads, isn’t it just a rearrangement how we build up the pairs? Of course it is:

implicit def associavityForProduct[A, B, C] = new Isomorphism[A * (B * C), (A * B) * C] {

def a2b = { case (a, (b, c)) => ((a, b), c) }

def b2a = { case ((a, b), c) => (a, (b, c)) }

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String * (Int * Boolean), (String * Int) * Boolean].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Unit a * 1 = a

Constructing a product is a binary operation on types. Given it is associative, if we could define a unit for it, an identity element, we could convince ourselves that it is monoidal somehow. Let’s do that.

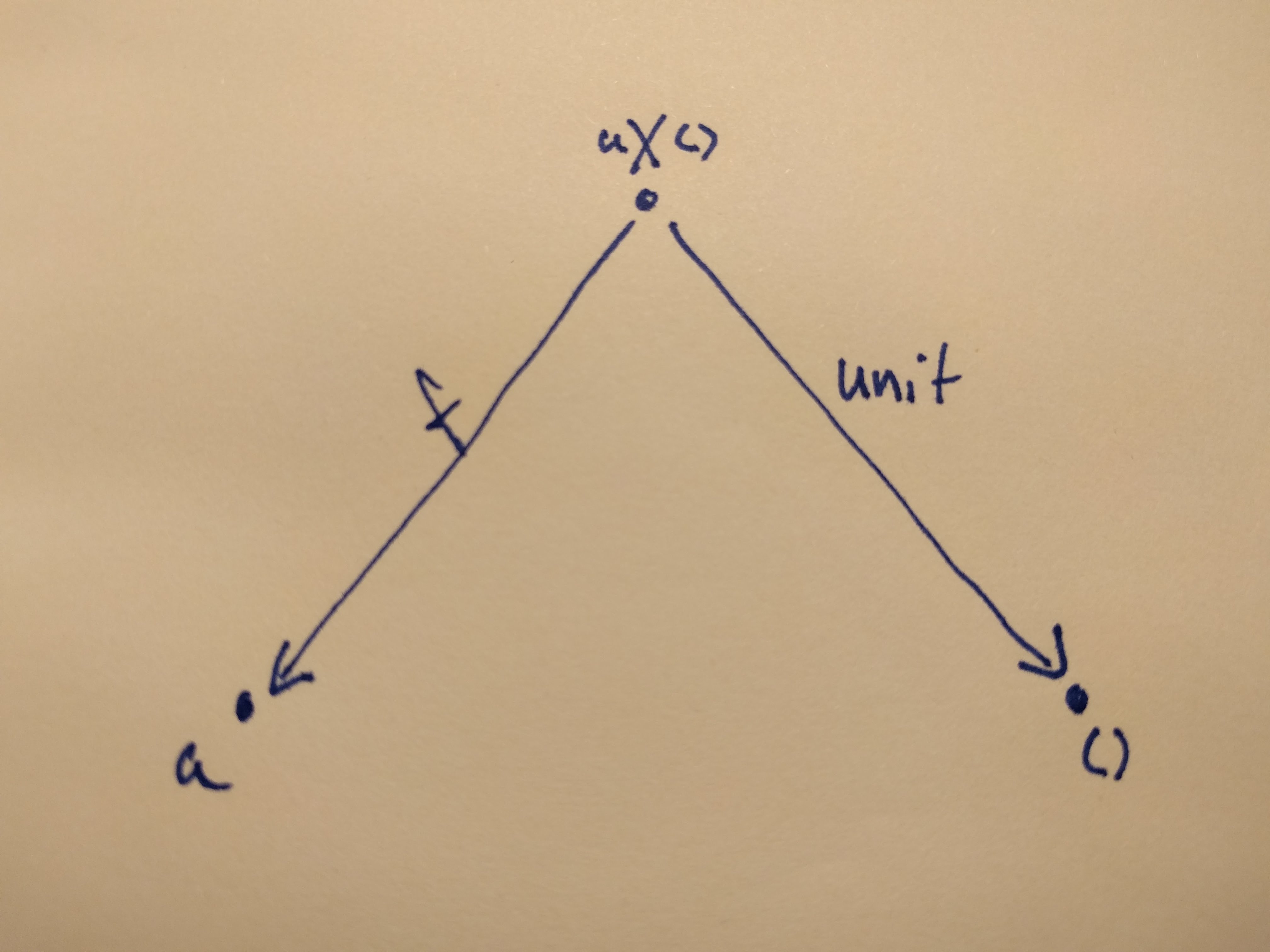

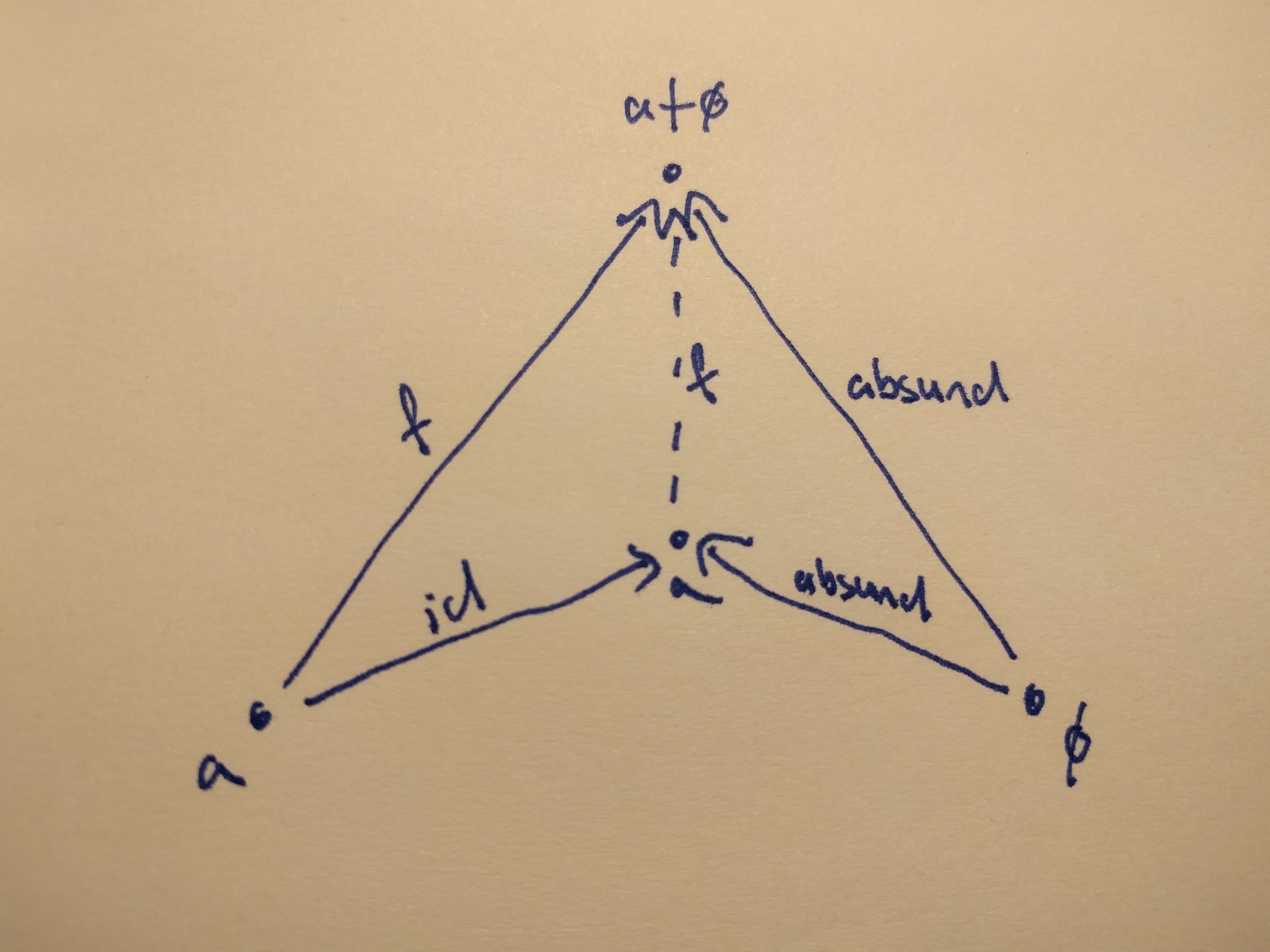

It turns out, that we can use the terminal object for this. Shockingly, the object itself is a better product candidate for itself and the terminal object, than any other object, and this falls out of the universal construction of a product. Let me show this. First, here is our figure with some a x () object being the product of a and the terminal object (()).

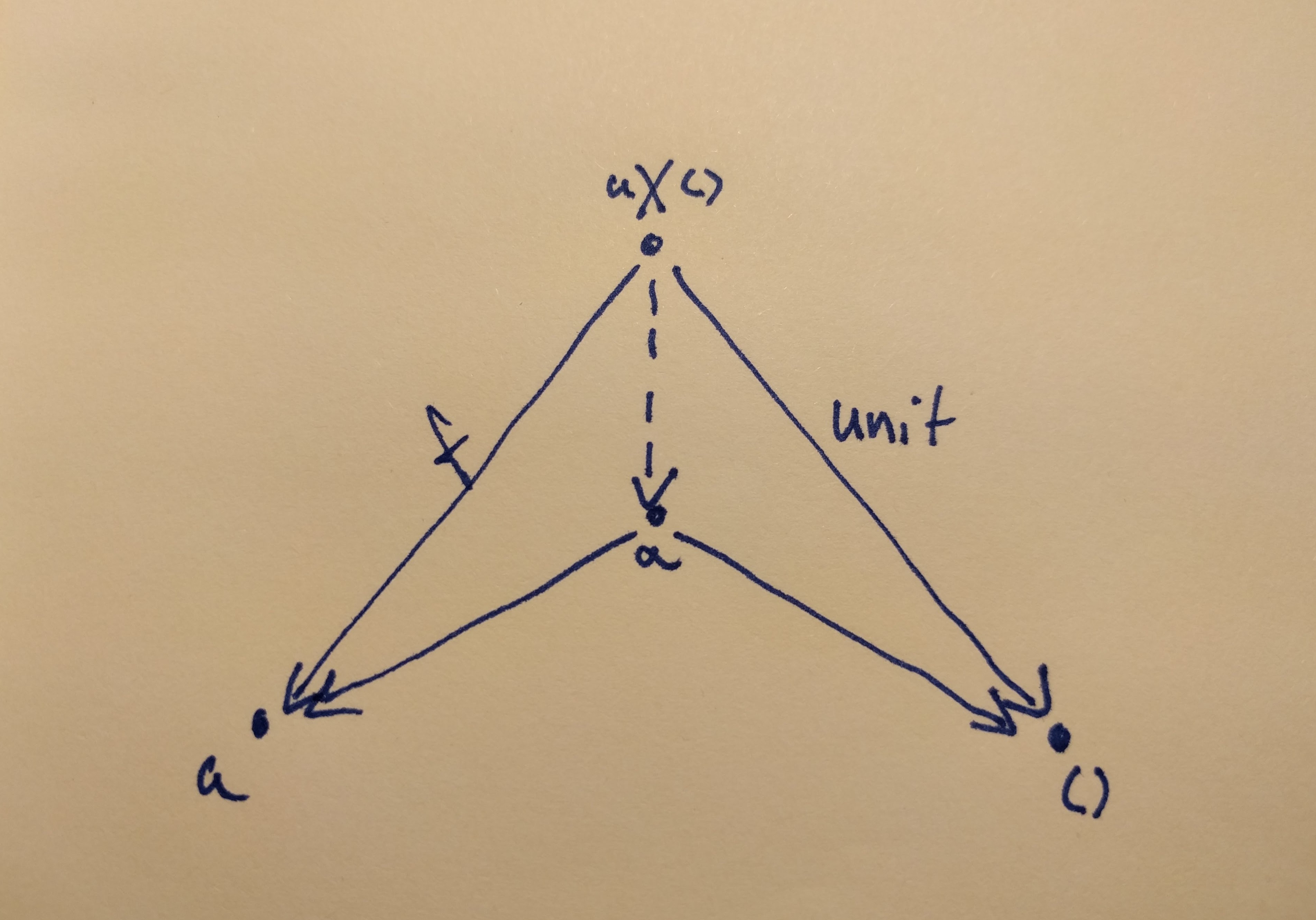

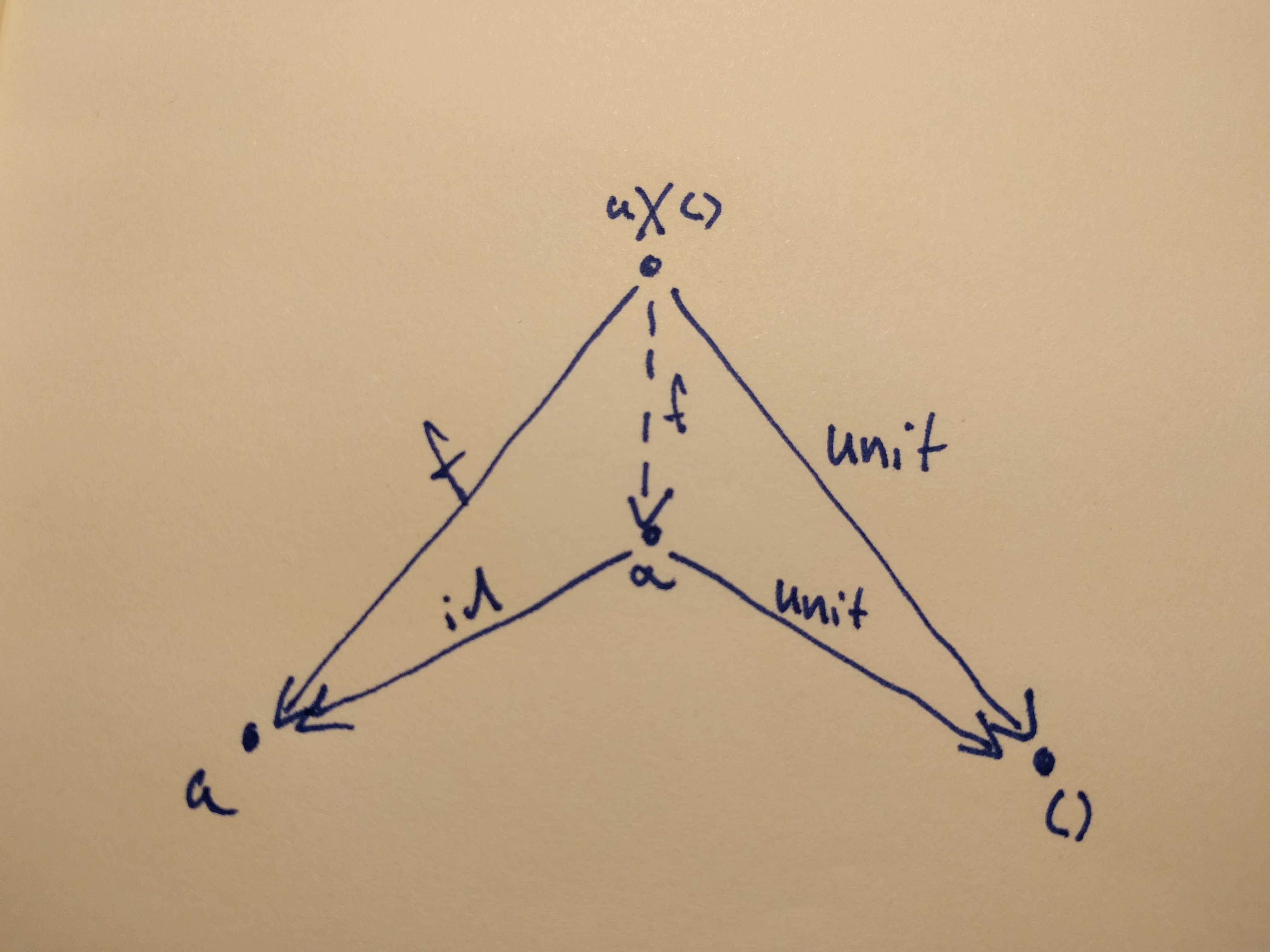

We want to show that a itself is a better candidate for this product

The only thing at our disposal is the universal construction. In order to prove that a is a better candidate, we have to find a morphism from a to a and to the terminal object, and from a x () to a as well.

Lucky for us, these morphisms are right there: a to a is id, the terminal object by definition has a unique morphisms from every other object in the category (we called it unit), and as for a x () to a, it is right there, we called if f.

In code, we want to show that A * 1 is isomorphic to A. What is 1 in this? A type with one and only one inhabitant, the terminal object, Unit 1

type One = Unit

implicit def unitOfProduct[A] = new Isomorphism[A * One, A] {

def a2b = projectFst

def b2a = (_, ())

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String * One, String].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Algebraic properties of coproducts

Commutativity a + b = b + a

Based on our experience swap-ping products, this will be easy. Why don’t we call it flip this time?

def flip[A, B]: A + B => B + A = {

case Left(a) => Right(a)

case Right(b) => Left(b)

}

implicit def commutativityForSum[A, B] = new Isomorphism[A + B, B + A] {

def a2b = flip

def b2a = flip

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String + Int, Int + String].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Associativity a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c

Again, basically this is just a rearrangement, maybe a bit more verbose, but if we follow the types, the code writes itself.

implicit def associavityForSum[A, B, C] = new Isomorphism[A + (B + C), (A + B) + C] {

def a2b = {

case Left(a) => Left(Left(a))

case Right(Left(b)) => Left(Right(b))

case Right(Right(c)) => Right(c)

}

def b2a = {

case Left(Left(a)) => Left(a)

case Left(Right(b)) => Right(Left(b))

case Right(c) => Right(Right(c))

}

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String + (Int + Boolean), (String + Int) + Boolean].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Unit a + 0 = a

For product the unit was the terminal object and for its dual the unit is the terminal object’s dual: the initial object. The reasoning is the same, just the arrows are reversed.

Where ø denotes the initial object. We want to prove that a is a better candidate for a coproduct than a + ø is.

Again, we can only use the universal construction, for which we have to find our injections and a morphism from a to a + ø. And they are, again, right there!

Now regarding the code, we will show that A + 0 is isomorphic to A. We declared Nothing to be our initial object, but, unfortunately, we would get stuck with a compile error2 if we used Nothing for our proof.

That’s not a problem, we can come up with an initial object in no time, we just need an uninhabited type. An abstract final class will be perfect.

import org.scalacheck.{Arbitrary, Gen}

abstract final class Zero

implicit val arbitraryZero: Arbitrary[Zero] = Arbitrary(Gen.fail)

implicit def unitOfSum[A] = new Isomorphism[A + Zero, A] {

def a2b = {

case Left(a) => a

case _ => throw new IllegalStateException("The world has just blown up, there is an instance of Zero")

}

def b2a = injectLeft

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String + Zero, String].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

The distributive property a * (b + c) = a * b + a * c

Now that one is interesting. My first reaction to this was “Noooo waay… but how? …wow, that’s cool”

implicit def distributivity[A, B, C] = new Isomorphism[A * (B + C), (A * B) + (A * C)] {

def a2b = {

case (a, Left(b)) => injectLeft((a, b))

case (a, Right(c)) => injectRight((a, c))

}

def b2a = {

case Left((a, b)) => (a, injectLeft(b))

case Right((a, c)) => (a, injectRight(c))

}

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[String * (Boolean + Int), (String * Boolean) + (String * Int)].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

Algebraic data types

Algebraic data types are built from products and sums. The product do not have to be implemented as a pair, and the sum do not have to be an Either. We can come up with a product type like this: case class Product[A, B](a: A, b: B) and it is just as fine as the tuple we used before. For sum types, although dotty has a Haskell-like syntax, in scala we use sealed traits for now. For example:

sealed trait Coproduct[A, B]

case class One[A, B](a: A) extends Coproduct[A, B]

case class Other[A, B](b: B) extends Coproduct[A, B]

Now we know why they are called algebraic.

Some extras

Remember what was the first code snippet that was used to try the isomorphism in the [previous post]?

We proved that Either[Unit, A] is isomorphic to Option[A]. Option is indeed an algebraic data type, and it is a sum of None (isomorphic to Unit) and Some[A] (isomorphic to A). To use this kind of notation: o(a) = 1 + a

What about a List?

A list is a sum of Nil, and Cons[A] where Cons[A] is a product of A and List[A].

l(a) = 1 + (a * l(a))

And, indeed, if we use substitution, we define all lists possible:

l(a) = 1 + (a * l(a))

= 1 + (a * (1 + (a * l(a))))

= 1 + a + a*a * l(a)

= 1 + a + a*a * (1 + a * l(a))

= 1 + a + a*a + a*a*a * l(a))

And so on, and so on. Isn’t it beautiful?

Next time, we will have a look at functors, stay tuned!

-

In the REPL I could not manage to use actual numbers as type aliases as I did in the repo ↩

-

error: diverging implicit expansion for type org.scalacheck.Arbitrary[String + Nothing]I am not sure why this happens, but I believe it has something to do with the fact thatNothingis a subtype of everything else. ↩

miklos.blog

miklos.blog