Adventures in Category Theory - Introduction

This post is the first in a planned series about my adventures in category theory. The plan is that as I build my understandings, I post a note here. I roughly follow Bartosz Milewski’s series on the topic and I translate the ideas to scala along the way. For in-depth and lengthy explanations I recommend visiting Bartosz’s blog, or watch him teaching category theory in a classroom, or dive into Saunders Mac Lane’s Categories for the Working Mathematician. I also started a repo a few weeks back, where I experiment with all this stuff and when I feel a piece of code is ready, I show it here.

Why bother?

The short answer is: “Why not? It looks like fun!” But one might expect some more detailed argument here.

Composition. Category theory is all about composition. It is even in the definition of a category. All day, every day we solve problems by decomposing them to smaller problems, solving those and then combine these pieces of software into greater units to solve the larger problems. That is what we do. Remember how John Hughes argued in his well known paper Why Functional Programming Matters that ‘the ways in which one can divide up the original problem depend directly on the ways in which one can glue solutions together’, everything that helps us composing things is our friend.

Abstraction. Abstraction is important, because nobody wants to deal with those pesky details all the time. It is much better when it is possible to express the ideas instead of implementation details, ideas are so much easier to reason about. The problem is, that finding the right abstractions is hard. Really hard. I am sure that all of us have failed miserably with this before. Mathematicians found great abstractions for us, haskell has been harvesting these ideas for a few decades now, and they are slowly leaking into other languages as well.

What I do love about category theory is that it is not some framework, or design pattern, or best practice that somebody came up with empirically because it helped them solve their problem, but it has strong mathematical foundations. It always adds up, things click smoothly, and it is just so satisfying and fun to experience this. We need foundations that strong and proven to move forward, as Bartosz has put it with this great analogy:

There is an unfinished gothic cathedral in Beauvais, France, that stands witness to this deeply human struggle with limitations. It was intended to beat all previous records of height and lightness, but it suffered a series of collapses. Ad hoc measures like iron rods and wooden supports keep it from disintegrating, but obviously a lot of things went wrong. From a modern perspective, it’s a miracle that so many gothic structures had been successfully completed without the help of modern material science, computer modelling, finite element analysis, and general math and physics. I hope future generations will be as admiring of the programming skills we’ve been displaying in building complex operating systems, web servers, and the internet infrastructure. And, frankly, they should, because we’ve done all this based on very flimsy theoretical foundations. We have to fix those foundations if we want to move forward.

What is a category?

A category consists of objects and morphisms (or arrows) between these objects. An object can be anything, it has nothing to do with the term we are familiar with from programming.

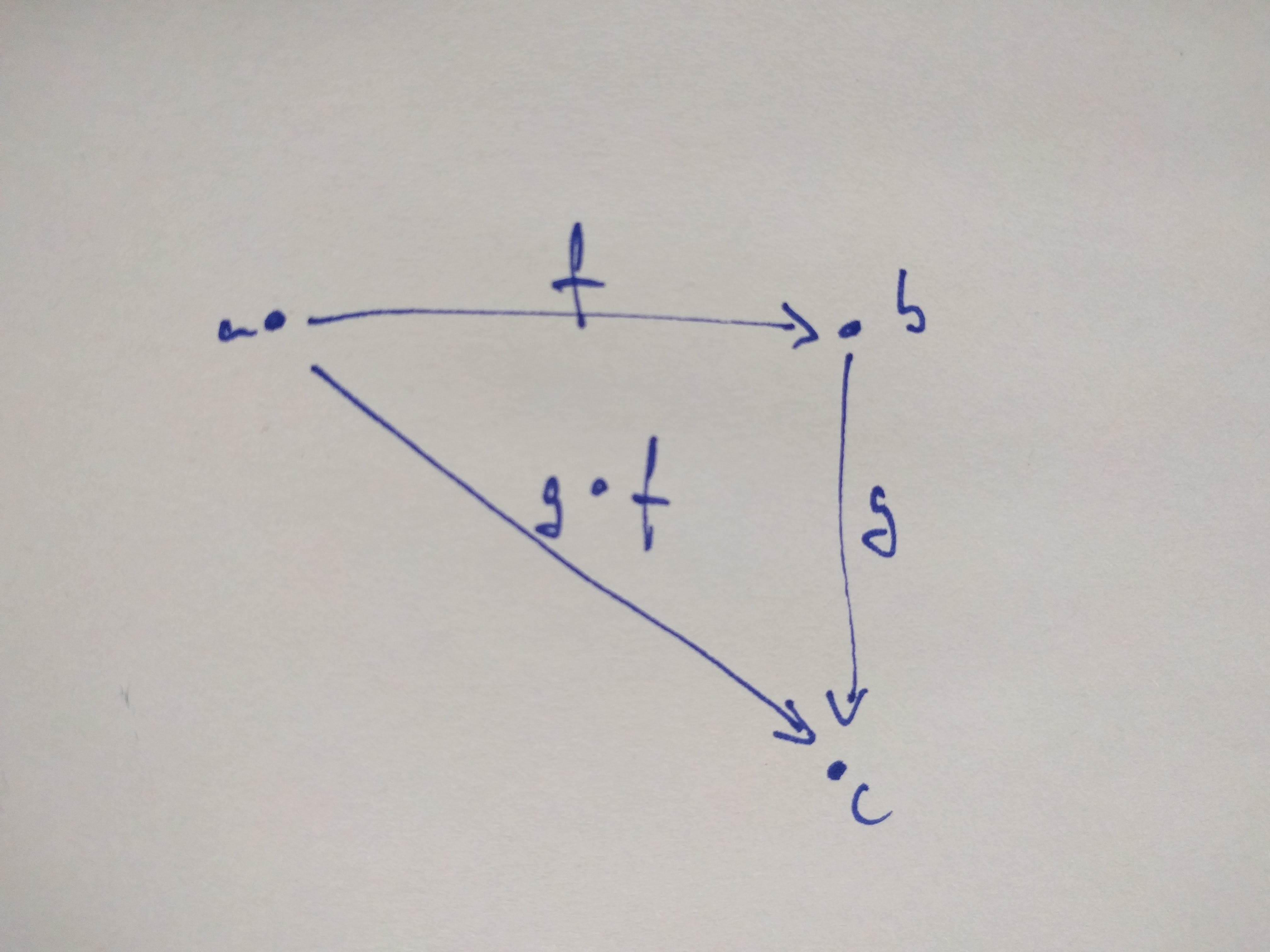

And the essence is composition. Arrows compose, so if we have an arrow from object a to object b called f and an arrow from object b to object c called g, then we can obtain an arrow from a to c called h by composing those two arrows together h = g ◦ f.

We can think of a category as a graph with some special rules.

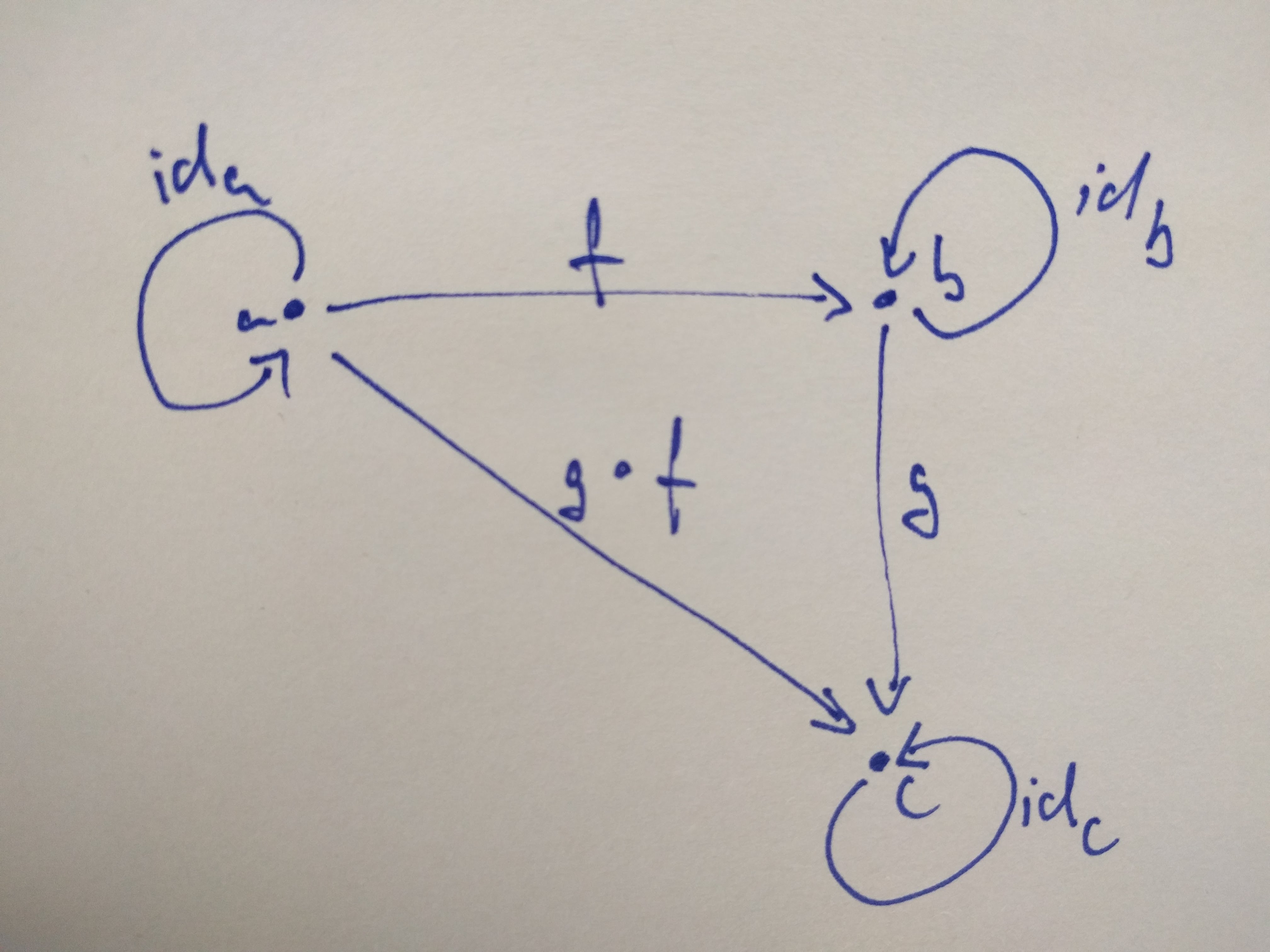

Identity

Every object must have an identity arrow (id), which goes from itself to itself. Composing the id with other arrows does not change anything.

id ◦ f = f and f ◦ id = f

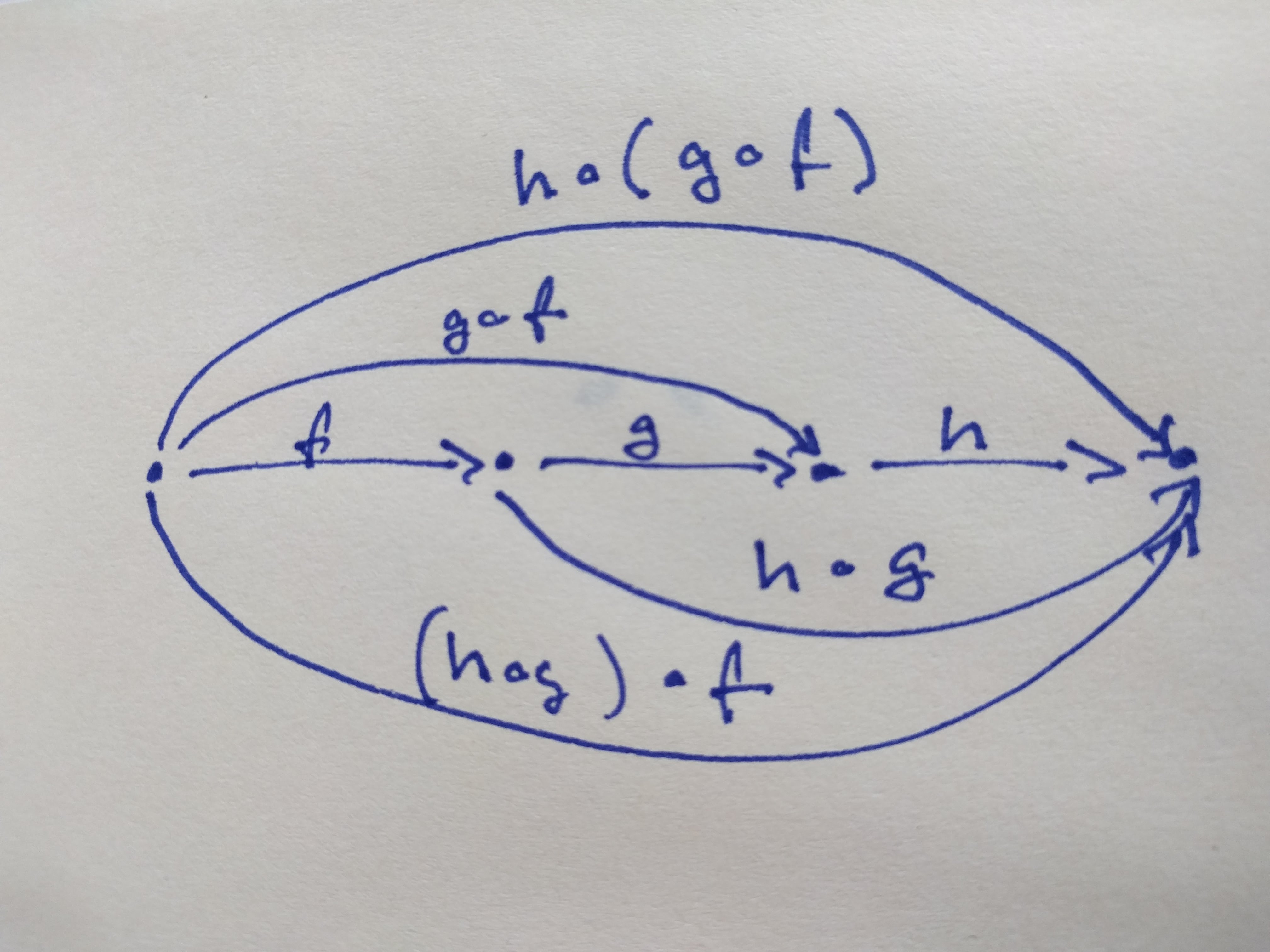

Associativity

Arrow composition is associative, so given three arrows: from a to b , from b to c and from c to d, then it does not matter if we obtain the arrow from a to d by composing the first two together first and composing that with the third, or the other way around.

(f ◦ g) ◦ h = f ◦ (g ◦ h) = f ◦ g ◦ h

And that’s it, there’s nothing else to it, really.

We will mostly talk about the category in which the objects are types from a programming language, and the arrows are the functions between them. It really is a category of sets. We can think of the types as sets (their elements are the possible values of a given type), so arrows become functions between sets. Were the types and functions from haskell, this category would be called Hask, but this series will present code samples in scala, so it does not have an official name I think. Scal? Skøl?

Simplest categories

The empty category

The category with zero objects - and therefore zero morphisms - is the most trivial one. It may not make sense for now, but as the number zero makes sense, or the empty set makes sense, so does this. The rules of identity and composition must still hold, and they do implicitly. Every one of the zero objects has an identity, and every morphism out of zero compose associatively.

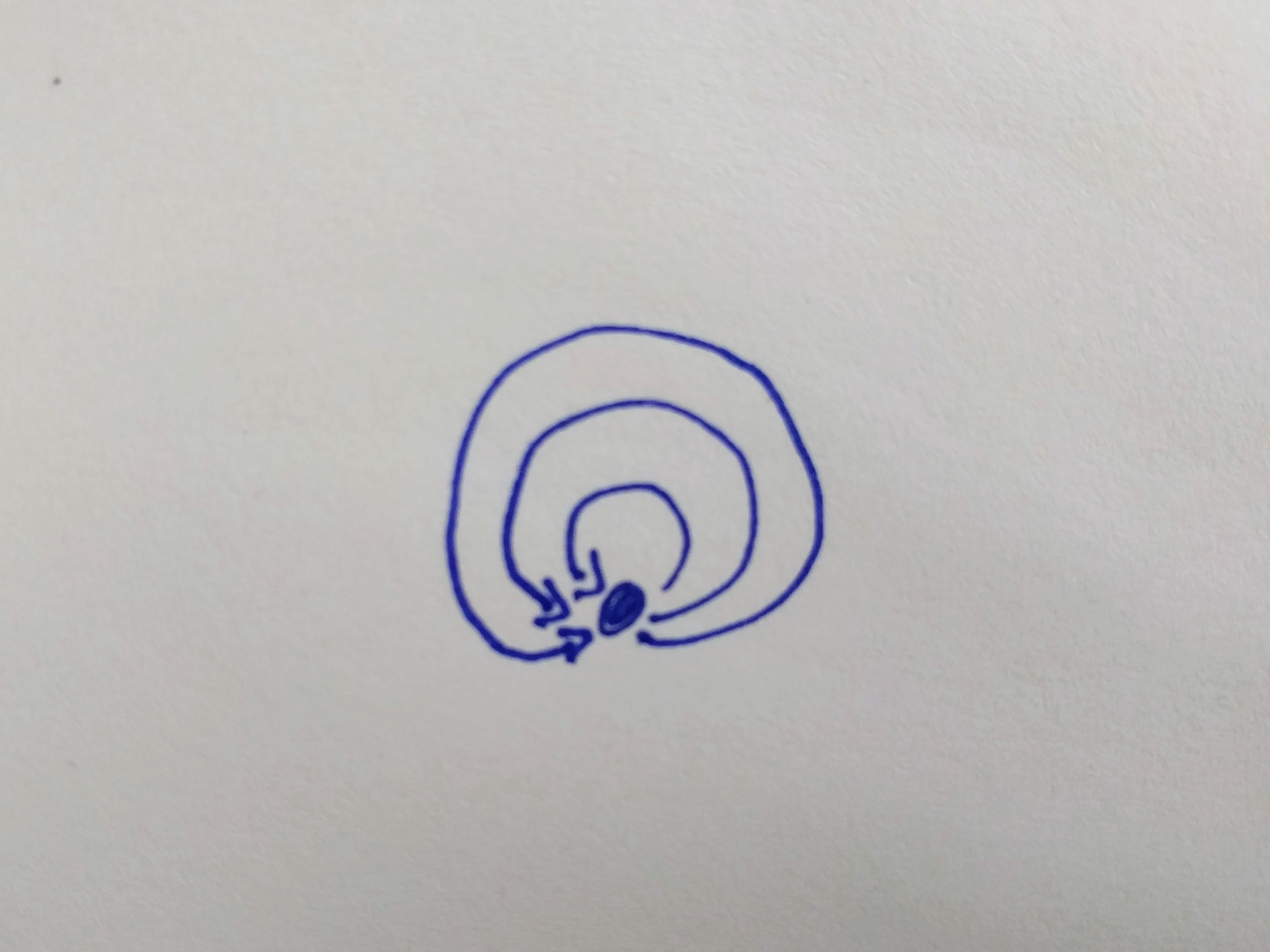

Monoid

Every category with a single object is called a Monoid. The reader is likely familiar with the concept of a Monoid from programming. It is defined for a type with an associative binary operation identity element (or zero, or unit), which does not affect the result of the binary operation in any way. The most common examples are addition for integers with the identity element being 0, or multiplication with the id 1 or string concatenation with the id being the empty string.

So how does it maps to category theory? I like to think about it that the single object is the type, the arrows are the elements of that type, with the identity element corresponding to the identity arrow, and the binary operator is the composition of arrows.

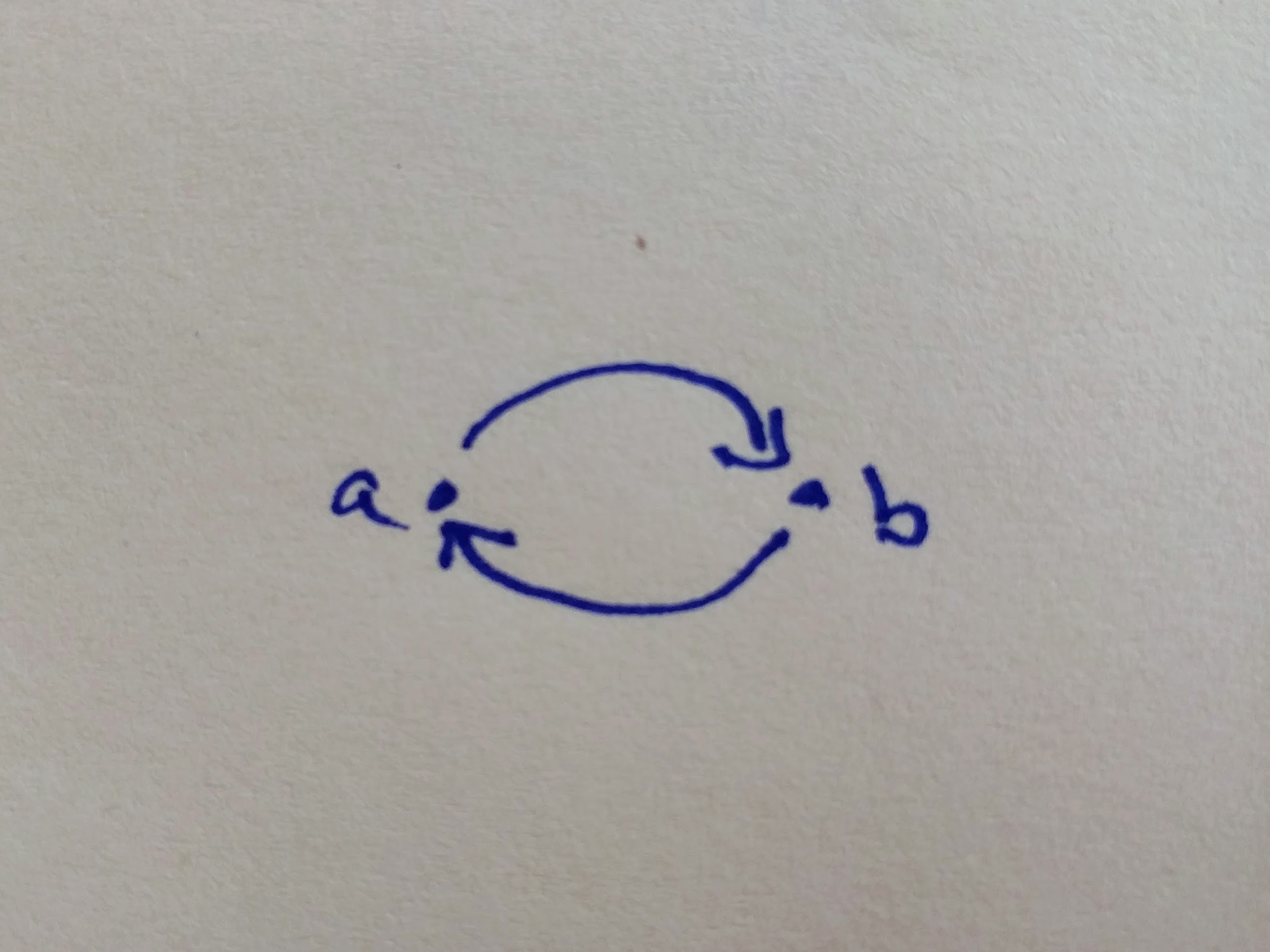

Isomorphism

Deciding about two things being equal or not is not trivial in programming, and it is not trivial in mathematics either. In category theory, we don’t really need equality, it is good enough if two objects are isomorphic. This means that objects a and b are isomorphic, if there is an arrow from a to b, say, f and an arrow from b to a, say, ‘g’, so composing f and g is the same as the identity arrow.

f ◦ g = id and g ◦ f = id

One way to express this in scala is the following trait and we can also introduce some fancy type alias for it.

trait Isomorphism[A, B] {

def a2b: A => B

def b2a: B => A

}

object Isomorphism {

type <=>[A, B] = Isomorphism[A, B]

}

See the definition of Isomorphism in my repo for some handy derived instances and syntactic sugar

But given an instance of an Isomorphism, how do we prove that the two types are indeed isomorphic? The definition is that if we do a round trip, we get an arrow that is identical to identity, let’s use that! So we will need something that can test if two arrows - two functions - are equal. Two functions are equal, if they produce the same output for the same input, that is as close as we can get, I think. We will use scalacheck for proving properties like this.

import org.scalacheck.Arbitrary

import org.scalacheck.Prop.forAll

import Isomorphism._

def arrowsEqual[A : Arbitrary, B](f: A => B, g: A => B) = forAll { a: A =>

f(a) == g(a)

}

def arrowIsIdentity[A : Arbitrary](f: A => A) = arrowsEqual[A, A](f, identity)

def proveTypesAreIsomorphic[A : Arbitrary, B](implicit ev: A <=> B) =

arrowIsIdentity(ev.a2b andThen ev.b2a)

Let’s try this one out with, for example, with proving that Either[Unit, A] is isomorphic to Option[A]. The definition of the isomorphism will almost write itself.

implicit def evidence[A] = new Isomorphism[Either[Unit, A], Option[A]] {

def a2b = {

case Left(_) => None

case Right(a) => Some(a)

}

def b2a = {

case None => Left(())

case Some(a) => Right(a)

}

}

proveTypesAreIsomorphic[Either[Unit, String], Option[String]].check

// + OK, passed 100 tests.

That was fun, next time we will have a look at products, coproducts and the algebra of types. And we will rely heavily on isomorphisms.

miklos.blog

miklos.blog